What Do You Call 101 Hidden Islands in Quebec?

Literature-inspired naming of land in the remote Caniapiscau Reservoir has caused controversy.

The Caniapiscau Reservoir lies 400 miles down a gravel road in northern Quebec—the most remote place in North America still accessible by car. It was here that fur traders established a Hudson’s Bay trading post in 1834, and where in 1976 Hydro-Québec began building a series of dams and dikes, part of the massive James Bay hydroelectric project. And it is here, among the black spruce of the boreal forest, that the intrepid traveler finds the Garden at the End of the World.

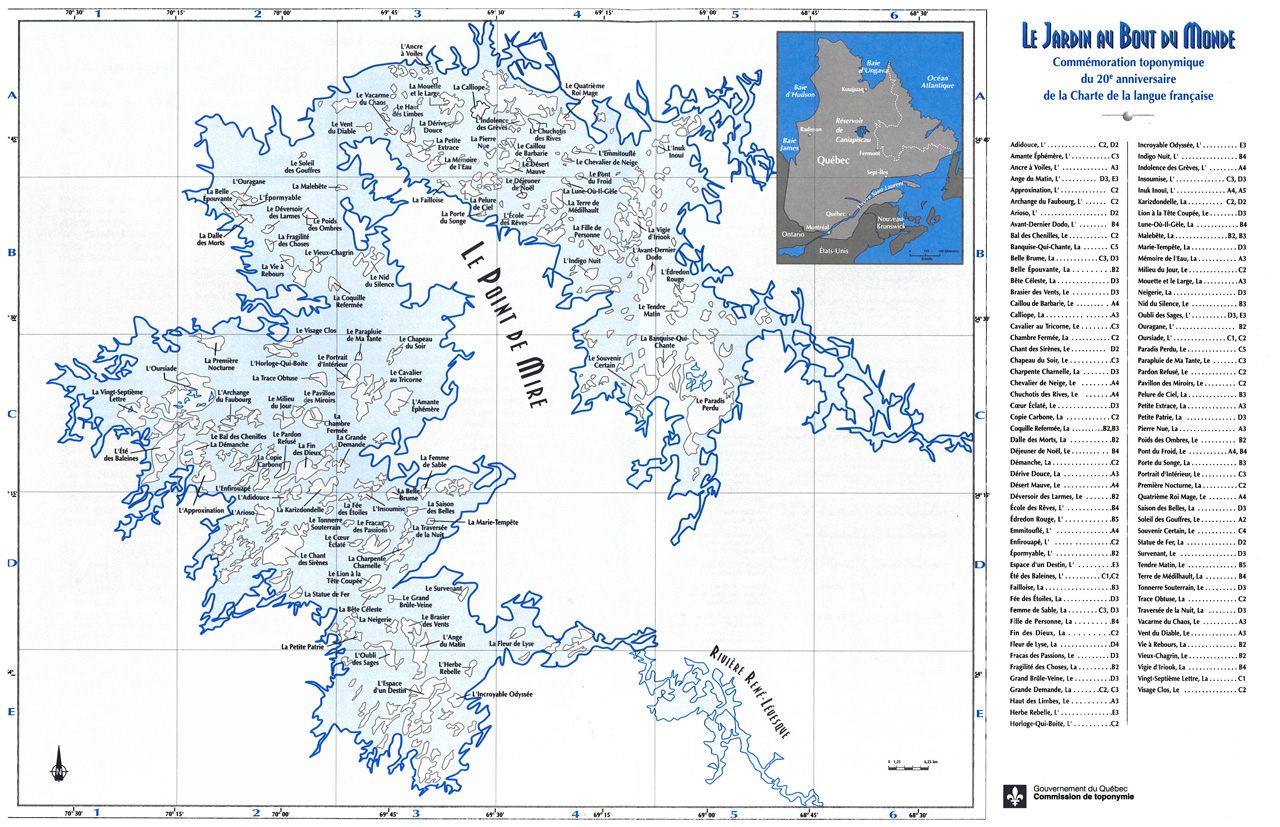

Even without a daylong journey through the wilderness, one can experience the garden, a metaphoric collection of 101 place names spread across 101 islands, through Le Jardin au Bout du Monde, a map the Commission de toponymie du Québec published in August 1997. Taking its name from a novel by French Canadian writer Gabrielle Roy, the blue and white map represents an area of about 350 square miles, with rough coordinates for each of the islands. In the upper right, a small inset positions the garden in relation to Montreal and Quebec City, while offering a politically charged view of Quebec and Labrador: the former implicitly lays claim to the latter through the use of light grey, which visually downplays a long disputed border. Beyond that, the map makes no reference to the gravel road and Hydro-Québec landing strip that link the Caniapiscau Reservoir to the outside world, nor does it include much else of cartographic value. As a wayfinding device, Le Jardin operates less in geographic reality and more in carto-literary make-believe—an imaginary map that bears the imprimatur of the Province of Quebec.

The toponymy commission, the provincial authority responsible for place names throughout Quebec, conceived of Le Jardin as a poème géographique that would give cultural dimension to “public lands in a landscape remodelled by human acts” while commemorating the 1977 Charter of French Language, commonly known as Bill 101. Nine commissioners selected the toponyms from fiction and verse published since World War II—what they considered “the most prestigious manifestations of Québécois language and literature.”

Whether on the ground or on paper, Quebec’s geographic poem presents a narrow view of the provincial oeuvre: The majority of place names originate from works by native-born francophones. La Fleur de Lyse, for example, comes from a line in Félix Leclerc’s song “Le tour de I’île,” while Le Nid du Silence comes from Gilles Vigneault’s poem “L’Immigrant.” A smaller number of islands honor work by French-speaking newcomers, such as Haitian-Canadian Dany Laferrière. Commissioners derived just three names from English-language works, albeit in translated form, while La Lune-Où-Il–Gèle alludes to the only First Nations book included on the map, La Saga des Béothuks (written, incidentally, by novelist and toponymy commissioner Bernard Assiniwi). Read as a whole, the mapmakers explained in the commission’s Toponymix newsletter, the new place names tell the story of “flowers that escaped from the garden of the imagination and tumbled into the Garden at the End of the World, animating the anonymous.” They also literally, figuratively, and officially put authors on the map.

Today, the map’s simplistic design, along with the purple prose that framed its release 20 years ago, belies the controversy that surrounded it upon publication. In fact, the announcement of Le Jardin proved immediately contentious in a province not yet two years removed from the sovereignty referendum of 1995, in which Quebec residents narrowly voted against leaving Canada. Literary-minded anglophones objected to the exclusion of English-language works by Leonard Cohen, Mavis Gallant, and Hugh MacLennan, among others. The Montreal Gazette, for example, ran dozens of letters criticizing the toponomy commission for the cartographic and critical slight, as well as a sarcastic op-ed (reprinted across Canada) by novelist Mordecai Richler:

Seemingly, on Thursday, Aug. 21, my time had come at last. . . . I sat by the phone from morning to night, a list of my published books to hand, but the call never came. There was to be no room for me in La Jardin au Bout du Monde. The sapients who preside over the Commission de Toponymie, its primary job to re-christian Quebec places besmirched by Anglophone names, had found me wanting.

An embarrassing homonymic oversight at first blush, Richler’s verb “re-christian” wryly alludes to an even more troubling aspect of the map—the whitewashing of a region long inhabited and named by Indigenous peoples.

While bookish types in Montreal feigned disgrace, Cree and Inuit leaders expressed genuine outrage. Without consulting northern communities, they pointed out, distant government officials had rechristened Rabbit Mountain, Beaver Mountain, Our Grandfather Mountain, and scores of traditional sites that had become islands as the reservoir filled. In eschewing existing topographic knowledge in favour of contemporary Québécois literary nationalism, commissioners had taken a well-worn page from the colonizer’s playbook.

“This is a political move, an attempt to occupy our territory and rename it, rather than adopt local names,” Bill Namagoose, of the Grand Council of Crees, told The Gazette. “When you fight over territory or sovereignty, one of the important things is to have title to the names.” Leaders in Nunavik, the Inuit region of northern Quebec, expressed similar outrage, describing the project as a “naming assault” and an arbitrary attempt to “manufacture French history where there is none.”

A month after the map’s publication, the toponymy commission seemed to backtrack on the place names it had just codified. Under the Gazette headline “Iles 101: Quebec Admits Mistake,” geographer Christian Bonnelly doubled down on the province’s best intentions while understating any error: “We were convinced they didn’t have names,” he told the paper. “If the Crees have some names in their inventories, the commission will consider the file in light of this new information. It could lead to certain changes.” Ostensibly, the commission did not consider Le Jardin a “closed file,” and would attempt to catalogue and adopt traditional Cree names.

Of course, taking La Fleur de Lyse, Le Nid du Silence, or La Lune-Où-Il Gèle off the map would compromise the organizing principle of the map itself. Perhaps that is why the toponymy commission did no such thing: Today, those and 98 other fictional locales remain the official designations for 101 islands of the Caniapiscau Reservoir. Twenty years after the commission offered to “officialize the Cree names,” Quebec’s online place-name database continues to celebrate the 1997 map and makes no reference to competing designations. (When contacted recently, a spokesperson said it was not appropriate to revisit Le Jardin, but that the commission remained open to “enriching” other islands of the Caniapiscau archipelago with Indigenous names.)

Like all maps, Le Jardin au Bout du Monde is a cartographic bibliography, a charged document that reveals complex narratives about a place’s spirituality, stories, and contested history. It epitomizes the fraught marriage of cartography and literary nationalism—taking to extremes a long tradition of literary mapmaking that can be traced back to the late 19th century. Unlike most pictorial literary maps, however, the critical lens of Le Jardin bears the power of the state. By disregarding Cree and Inuit place names in favor of fictional ones, mapmakers casually—and officially—brushed aside traditions that root Indigenous people to the Caniapiscau region.

At the same time, Le Jardin demonstrates that once they appear on a map, imposed place names (and all of the complicated consequences they impart) have the tendency to stick. Indeed, as Martin Waldseemüller found when he erroneously christened an entire continent “America” in 1507, it is easy to place a name on a map—but much harder to remove it.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook