The Fight to Save Chile’s Glorious White Strawberry

The ancestor of the big red strawberry is in peril.

It’s nearly Christmas in the foggy Nahuelbuta Range of south-central Chile and berries the size and color of ping-pong balls are ripening in small gardens that tumble down steep forested slopes. The dwindling number of aging farmers who still cultivate these frutillas blancas have just five weeks to comb these gardens and harvest their goods. Five weeks to make a year’s worth of profit.

In that brief time, these white strawberries—which turn a pale pink when ripe—will have two local festivals in their honor. There will be white strawberry cooking competitions, beauty queen contests, and nightly folk music. The fragrant fruits, which have a pineapple-like fragrance, will find their way into custardy kuchen cakes, preserves, and, most importantly, clery, a sangria-like aperitif made with white wine. The drink will become a staple at every gathering between Christmas and New Year in this tiny enclave—the only place in the world that still cultivates these berries at scale.

“The white strawberries are like a link to our past,” explains Cristian Monsalve, the director of economic development for the Municipality of Purén, which has Chile’s largest concentration of white strawberry fields. “It’s part of the identity of this community, where there remains, to this day, an air of romance about being a white strawberry farmer.”

Ask about the frutilla blanca anywhere else in Chile and people blink their eyes, bewildered, especially if they’re under the age of 40. Despite its storied history in the nation, this native product is now on the brink of extinction. You can barely find it outside of the two regions where it’s still grown. It’s ironic, because the offspring these white strawberries spawned is everywhere: the large red strawberry that went off and conquered the world.

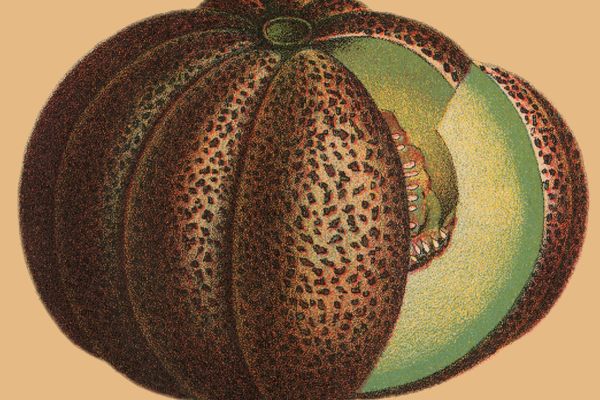

The white strawberry (Fragaria chiloensis subsp. chiloensis) is the mother, of sorts, to the strawberry found in the cakes, ice creams, and yogurts in global supermarkets. A French spy by the name of Amedée François Frézier carried five specimens back to Europe in 1714. Three decades later, in Brittany, they were crossed with the Virginia strawberry (Fragaria virginiana) of eastern North America to create the garden strawberry (Fragaria × ananassa) we all know today.

In a cruel twist of fate, the garden strawberry arrived back in Chile in 1830 and slowly, over the decades, came to dominate local fields, nearly wiping out a crop that had been grown there for centuries.

The indigenous Mapuche were the first to cultivate the white strawberries, which they call kelleñ. In addition to eating them raw, the Mapuche would dry them like raisins, prepare them in fermented chicha, and use them for traditional medicines to combat diarrhea, dysentery, and indigestion, mainly using the calyx of the plant, wrote anthropologist Héctor Manosalva. The fragrant aroma of the strawberries was also used to ward off the devil, or weukufu, who was believed to be repelled by all things sweet in the local mythology.

During the Arauco War (1550-1656), the Mapuche planted strawberries to lure Spanish soldiers into traps where they could ambush them. Historical records show that these conquistadors enjoyed this super-sweet fruit so much that they carried it to their new cities further north, planting the crop near Cuzco in Peru, Ambato in Ecuador, and Bogotá in Colombia.

The white strawberry has all but disappeared from these places now, as well as from much of its historic range in central Chile. In fact, it’s grown only in the high hills of two neighboring towns in the Nahuelbuta Range. Even in these towns, Contulmo and Purén, it’s such a rare delicacy that a kilo goes for 22,000 Chilean pesos ($28) compared to just 2,000 pesos ($2.50) for the garden variety.

Despite those prices, the market has been in steady decline. Cecilia Céspedes, an agroecological researcher with the Chilean government agency INIA, led a three-year project to help reverse the fate of the white strawberries. She explains that several factors contributed to their precipitous decline in recent decades.

The first blow was the closing of the Lebu-Los Sauces train line in 1985, which carted the white strawberries to Chile’s third-biggest city, Concepción, where they were a prized summer treat. With the closure of the train station, the lumber industry moved in, planting huge tracts of pine and eucalyptus which, local farmers argue, degraded the soil. These days, fewer than two dozen families remain as independent farmers, working on plots little more than an acre in size.

Climate change is the third and latest challenge. Winter snows that help induce flowering—and lead to bumper crops—are now increasingly rare. What’s more frequent are droughts, which are “tough for this sensitive crop, which has a low yield and short harvest,” Céspedes says. Whereas garden strawberries are harvested in Chile from October to April, white strawberries bear fruit only from December to early January at the start of the Southern Hemisphere summer.

Céspedes worked with the communities of Contulmo and Purén between 2015 and 2018, providing monthly workshops on how to improve plant health, raise yields, manage water use and, ultimately, how to band together to reconcile regional grudges and promote the product as a united force. Contulmo and Purén, though neighbors, lie in different regions, receive funds from different governments, and have a long-running rivalry over the white strawberry, which both claim as their own.

Despite all her work, which culminated in a 180-page book, Céspedes still fears for the white strawberry’s future. “The older generation is dying off and most of the younger generation have moved away,” she explains. Yet she points to 28-year-old Jairo Carvajal, a farmer who studied agronomy at the Catholic University of Temuco, as a glimmer of hope.

“My parents and their parents before them have all cultivated the white strawberry,” says Carvajal. That’s why, after getting his degree, he returned to Purén not only to continue the family tradition, but innovate farming techniques and draw interest to the crop.

“We need to continue expanding the production of this fruit—and making more people interested in it—so that this tradition isn’t lost,” he says. “After all, aside from being a native species, this is also something that’s very important for global conservation.”

Along with Carvajal’s activism, there are other promising signs on the horizon. A new tourism route, La Ruta de la Frutilla Blanca, has helped drum up some local interest in the white strawberries. Meanwhile, in the Chilean capital of Santiago, the nation’s most famous restaurant, Boragó, now uses white strawberries on its menu in ice creams and juices, and even as a seasoning for fish.

“We also make a special desert called tres leches y tres frutillas,” says Rodolfo Guzmán, Boragó’s head chef and owner. “Normally this classic Chilean dessert is really sweet, but ours is not. We use goat, donkey, and sheep milk and we make a semifreddo of white strawberries with sea strawberries and wild strawberries.”

Beyond Chile, there is definitely a market for unusual fruit. White strawberries even have a precedent abroad. In Belgium and the Netherlands, there is already a white strawberry known as the “pineberry” that’s become quite popular. In the U.S., pineberry goes by the name “hula berry” and made waves after appearing (in plant form) in stores like Home Depot and Walmart.

Like the garden strawberry, however, both of these fruits are a Fragaria x ananassa hybrid. They’re not the pineapple-scented fruit from Chile, which faces a future far less certain than the globe-trotting hybrid it bestowed upon the world.

Lovers of Chile’s frutilla blanca hope that, one day, strawberries can go through a process similar to that of grocery store apples, which used to be uniformly red before their colorful green and golden cousins helped diversify the market. Carvajal even argues that the sweet flavor of the white strawberry is far superior to that of the red one. The rest of the world, he says, just doesn’t know what it’s missing.

Gastro Obscura covers the world’s most wondrous food and drink.

Sign up for our email, delivered twice a week.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook