A Popular ’40s Map of American Folklore Was Destroyed by Fears of Communism

The government saw Red when looking at William Gropper’s painting of the United States.

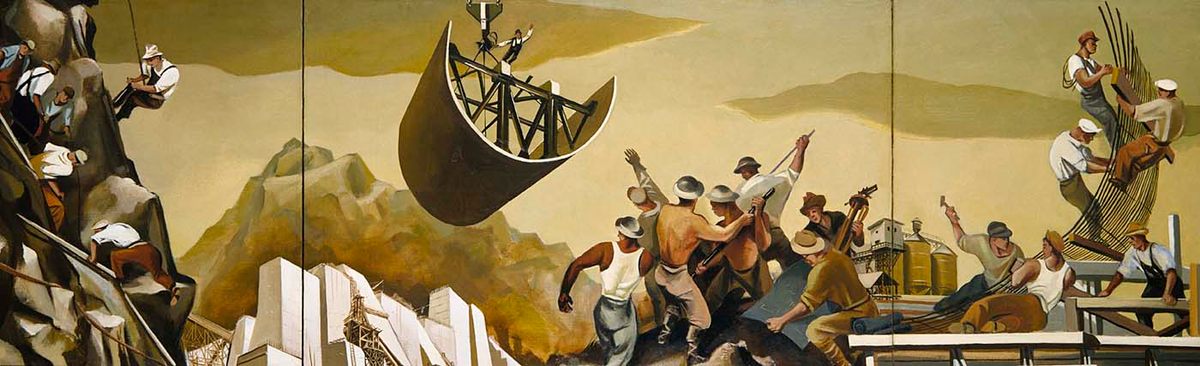

During World War II, the painter, illustrator, and cartoonist William Gropper offered his services to the U.S. Treasury Department and the White House’s Office of War Information. He received a “Citation in recognition of fine assistance” from the Treasury Department and personal thanks from Franklin Delano Roosevelt, for “giving pictorial form to specific war information objectives” through propaganda posters and paintings. It seemed logical that after the war, the State Department, too, would find value in the famous artist’s social-realist portrayal of American culture—a logic that would soon find Gropper trapped within the surrealist labyrinth of McCarthyism.

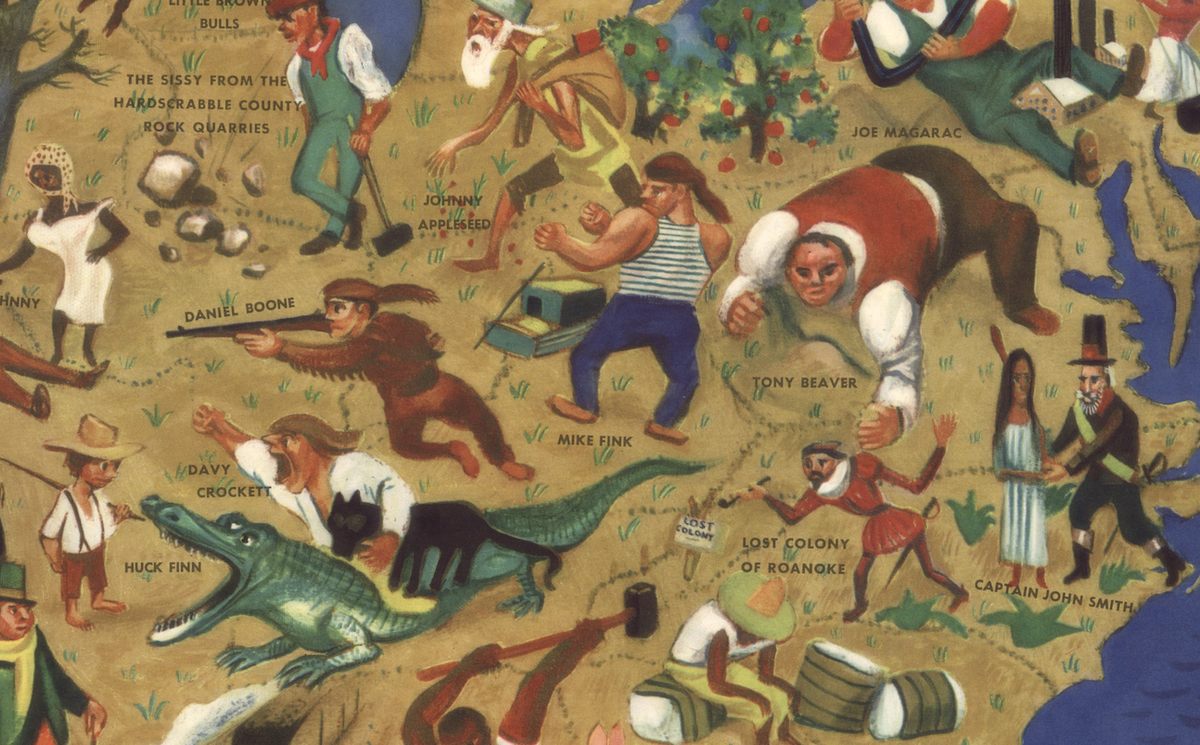

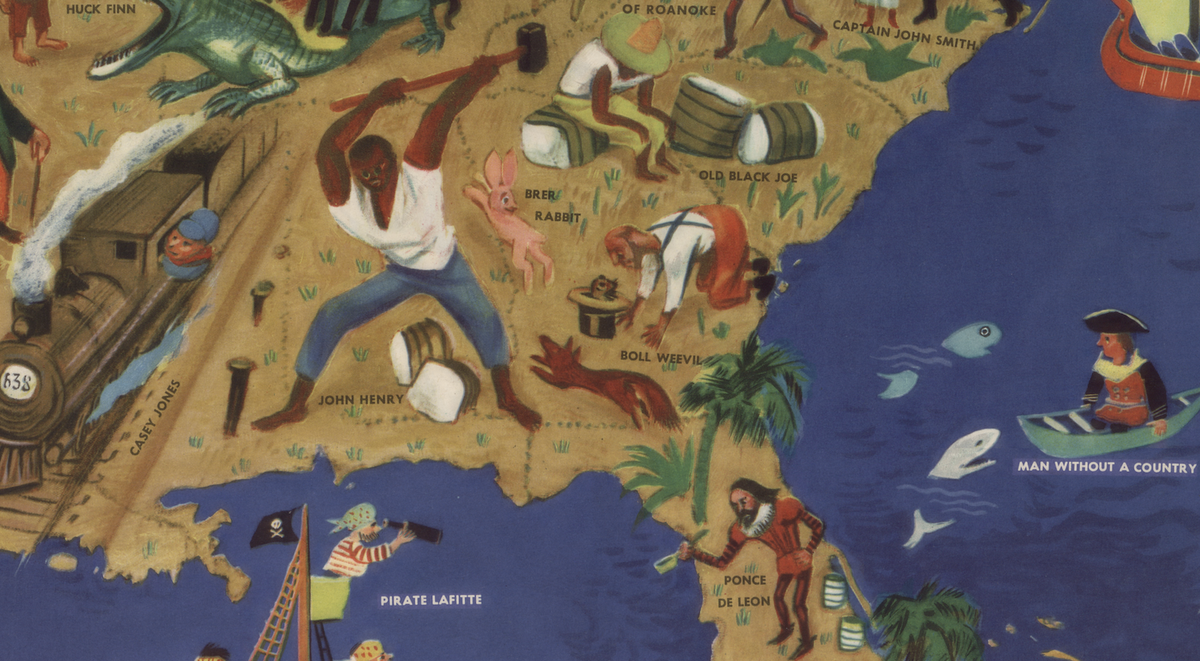

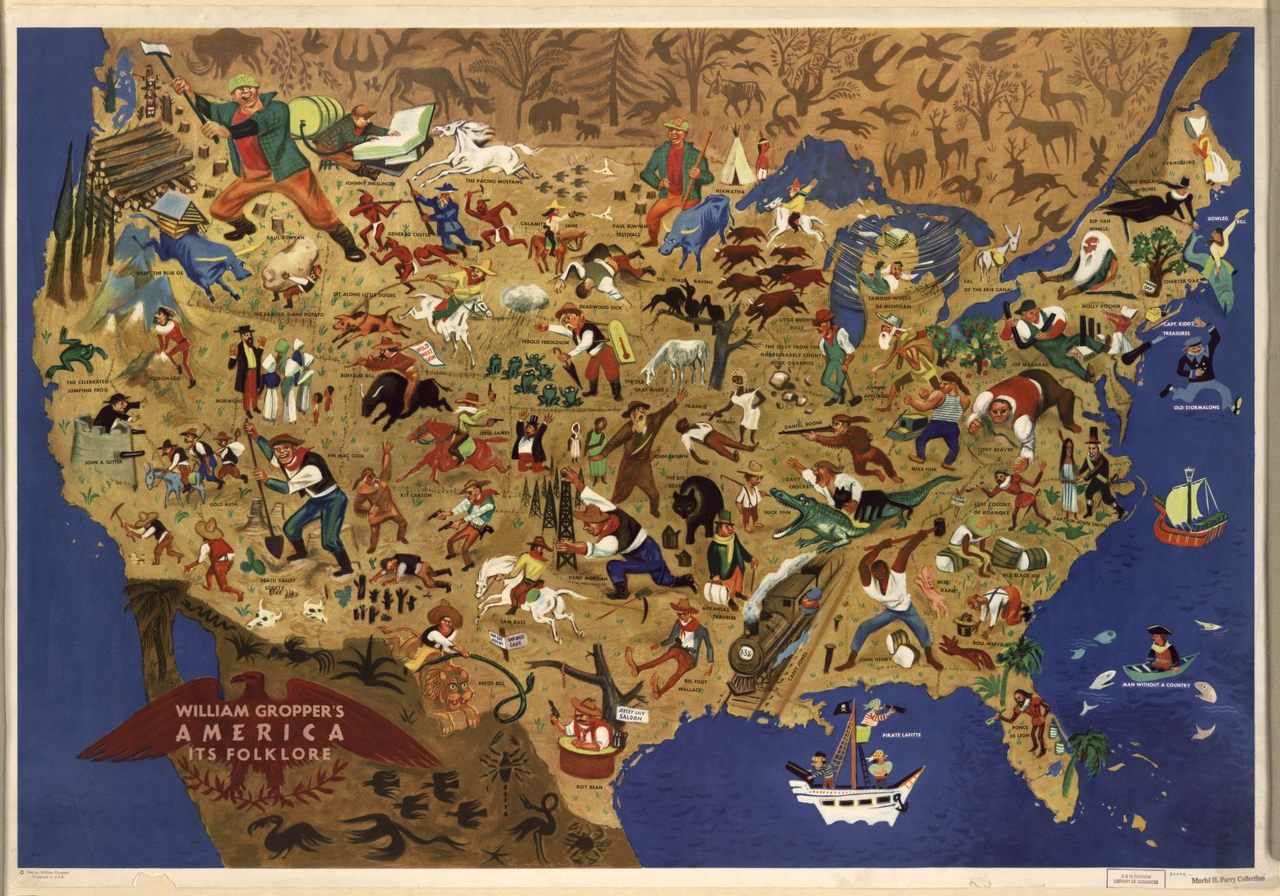

Between 1946 and 1953, the State Department’s Overseas Library Program collected and distributed some 1,744 copies of William Gropper’s America: Its Folklore, a colorful depiction of 61 legends, tall tales, and literary heroes—characters like super-sized cowboy Pecos Bill in New Mexico, steel-driving phenom John Henry in Alabama, and witty trickster Br’er Rabbit in Georgia—superimposed over a familiar projection of the Lower 48.

The purchase was part of postwar efforts to disseminate “facts and solidly documented explanations of the United States.” Based on a painting Gropper completed in 1945, the 34-by-23-inch pictorial map was published by Associated American Artists, and sold by mail order—$5.00 unframed, $14.50 mounted—in the New York Times, Life, and other popular publications. An accompanying 16-page brochure told viewers more about Paul Bunyan, Johnny Appleseed, and their folkloric ilk.

While the State Department exploited the map’s propaganda potential abroad—its playful characterization of America as a fun-loving, welcoming, and, most important, free land—librarians and teachers took advantage of its educational usefulness at home. Throughout the late ’40s and early ’50s, newspapers from coast to coast ran stories about students studying literature with the help of America: Its Folklore. Municipal libraries even lent framed copies, making it easy for students to show off their newfound knowledge at home.

But the cartographic darling fell from grace in the spring of 1953, when attorney Roy Cohn toured State Department libraries around the world as part of his and Senator Joseph McCarthy’s crusade against Communism. Cohn identified William Gropper as one of the “fringe supporters and sympathizers” whose supposedly Communist-directed works had infiltrated the Overseas Library Program. Gropper was promptly subpoenaed to appear before the Senate Permanent Subcommittee on Investigations—and earned the dubious distinction of being among the first blacklisted artists in McCarthy-era America.

Gropper arrived on Capitol Hill looking “as rumpled as the sofa in front of the television set,” as one commentator observed. Surrounded by Klieg lights, television cameras, police, and press, his interrogation began simply, with chief counsel Cohn asking, “Are you a member of the Communist Party?” As far as Cohn and McCarthy were concerned, they already knew the answer. But after the artist invoked the Fifth Amendment, refusing to answer so as not to bear witness against himself, Cohn pressed:

Mr. Cohn: Are you the William Gropper who has prepared various maps?

Mr. Gropper: I don’t understand that question. Prepared various maps?

Mr. Cohn: Did you prepare a map entitled “America, Its Folklore”?

Mr. Gropper: Have you got the map here?

Mr. Cohn: No; I don’t have the map here. Did you prepare a map entitled “America, Its Folklore”?

Mr. Gropper: I painted a map on American folklore, yes.

Gropper explained that he had received an advance from Associated American Artists, but that “no royalties came in.” Cohn wanted to know if part of Gropper’s advance had supported Communist causes. Again, Gropper pleaded the Fifth Amendment. When Senator Stuart Symington of Missouri asked the painter if an individual “could be a member of the Communist party and at the same time be a good, loyal American,” Gropper demurred: “I would rather talk about my field, where I am equipped. I don’t understand these things.” Moments later, Gropper tried to distance himself further from his celebrated pictorial map, explaining, “I don’t even make maps. I am a painter.”

No matter that Gropper had, in fact, tried his hand at mapmaking; no matter that Gropper was not, in fact, a Communist. The damage was done. The next day, the left-leaning, 55-year-old Jewish artist from Brooklyn found his name on the front page of national and local newspapers. The message sent down from McCarthy’s perch in the Senate was clear: William Gropper was a Red. His map was un-American.

There is nothing immediately offensive or subversive about America: Its Folklore. True, contemporary folklore purists may have taken issue with it for including so-called tall tales and legends that originated in print culture rather than oral tradition (Washington Irving’s Rip Van Winkle appears, for example, as do Mark Twain’s Jumping Frog of Calaveras County and E.E. Hale’s Philip Nolan). But to quibble with the American scene that Gropper depicted would be scholarly inside-baseball indeed. What matters is that overnight—thanks to what he would later describe as the “American Inquisition”—his work became the most notorious pictorial map in history.

Today extant copies of America: Its Folklore are exceedingly rare. The Library of Congress has two examples, while the Illinois State Library and the University of Michigan each have a copy, as do a handful of others. Well-loved survivors do surface from time to time—a paltry $9.99 on eBay in 2010, $120 from a pair of pickers in Michigan in 2017—but never with the original supplementary brochure.

One could argue that the blacklist led to the map’s erasure from popular culture, and there is some evidence to support that interpretation. The State Department systematically destroyed its 1,744 copies. Surely many domestic institutions did the same. But even after America: Its Folklore scandalized Washington and led to the downfall of its creator, teachers continued to use it in their classrooms.

Indeed, another way to explain the map’s scarcity today is through its enduring popularity yesterday. Teachers, librarians, and especially students literally used it to pieces (and most copies that do survive bear physical witness to that use). Perhaps the greatest testament to its contemporary appeal is the vacuum it left when thousands of copies were destroyed on purpose and countless more were destroyed by exchanging hands in classrooms, public libraries, and living rooms.

Within a year of Gropper’s Capitol Hill evisceration, the National Conference of American Folklore for Youth began selling a similarly sized, similarly whimsical American Folklore & Legends by John Dukes McKee, because, as the English Journal put it, teachers across the country “kept asking for [it].” And after that map went out of print a few years later, the General Drafting Company produced Frank Soltesz’s Folklore and Legends of Our Country in 1960 for distribution in Esso gas stations—the perfect cartographic distraction for kids in the back of the family station wagon, while their parents argued about politics.

Map Monday highlights interesting and unusual cartographic pursuits from around the world and through time. Read more Map Monday posts.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook