This Map Shows a Fictional Country Created by a Con Man

In the 19th century, Scottish scammer Gregor MacGregor made a fortune selling land in Poyais.

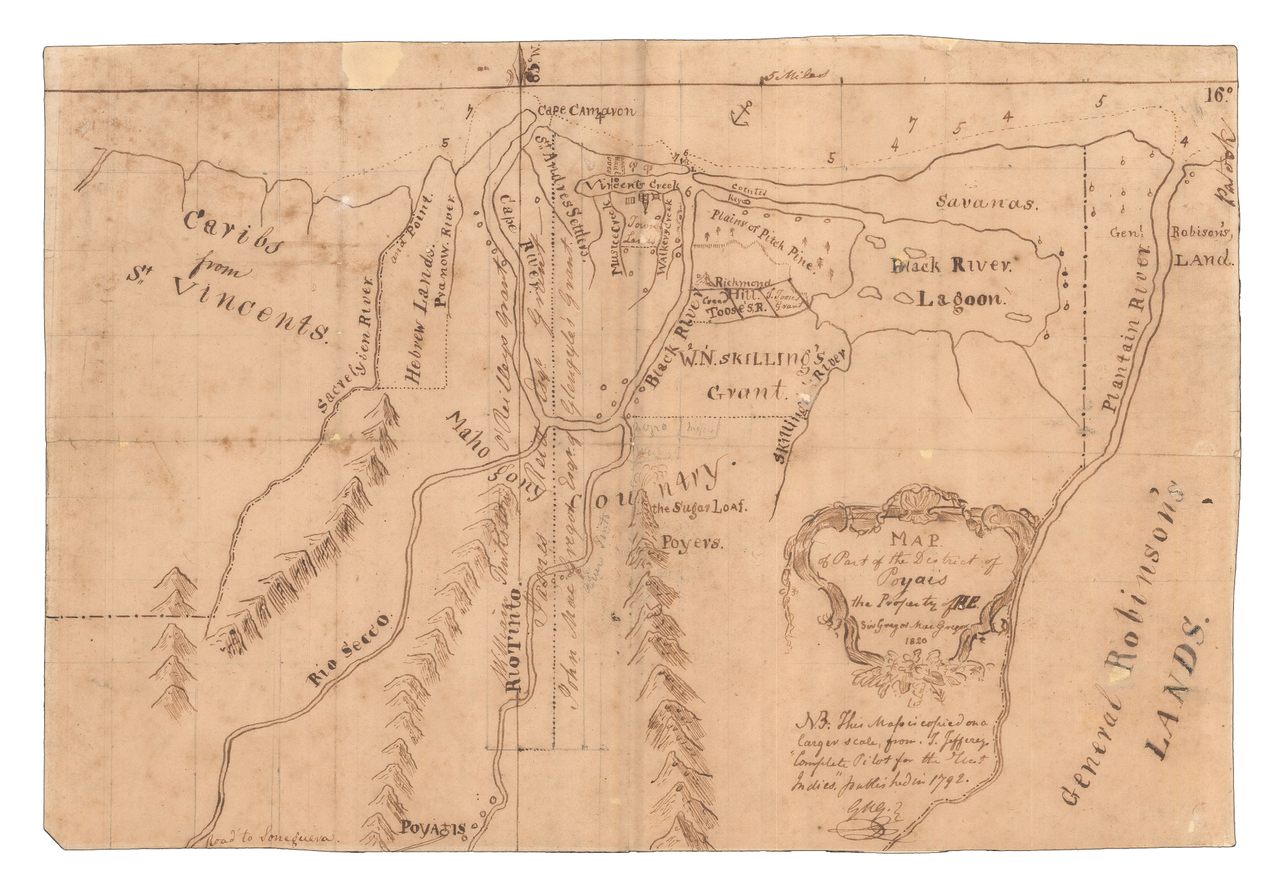

A little over a year ago, Daniel Crouch, one of the foremost dealers of rare books, maps, and atlases in the world, came into possession of a 19th-century map. It had been drawn by a man named Gregor MacGregor. “The first thing you need to know about Gregor MacGregor, from the Clan Gregor, is he’s improbably named,” says Crouch. “The second is that his story is so improbable, but, trust me, everything I’m about to tell you is true.”

The map depicts the Central American monarchy of Poyais, an oasis of around 8 million acres sandwiched between present-day Nicaragua and Honduras on the Mosquito Coast. Much of the small, tropical country runs right along the Caribbean. MacGregor’s map faithfully draws in the major port towns of St. Joseph, Lempira, and, of course, MacGregor, all abutting turquoise waters with lush forests behind them.

There’s just one catch: Poyais never existed.

MacGregor’s map was part of one of the most successful con jobs in human history. By the time it was over, this rakish Scottish swindler would trick hundreds of poor souls into investing in the fictional Scottish colony. In 1822 alone, MacGregor sold a £200,000 in Poyaisian government bonds, supposedly with 6 percent return. What’s more, from 1822 to 1823, he convinced seven ships worth of aspiring settlers to purchase land in the nation and uproot their lives.

Crouch, who runs a rare book shop in London, has been obsessed with maps as a tool for imaginary world-building for some time. His private collection features dozens of other places that never existed. In 2,700 Years of Fictional Cartography, an exhibit which ran at this year’s Frieze Masters in London, he included a 1665 map of Atlantis by Athanasius Kircher, a map of Hell from Dante’s Divine Comedy, and original maps from C.S. Lewis’s The Chronicles of Narnia and J.R.R. Tolkien’s The Lord of the Rings. The collection is in the process of transitioning to a permanent venue, tentatively slated to open next year.

“Like all good ideas, it started in the pub,” Crouch says. At the time, his daughter had been working at Blackwell’s, a bookshop in Oxford. “We did a pub quiz together every week. There was a round on fantasy fiction, which obviously we aced. We started a conversation about how all good fantasy books start with a map.”

After all, Tolkien himself declared, “I wisely started with a map, and made the story fit.” Once the author had sketched out the confines of Middle Earth, he was able to envision characters to populate it. He was hardly alone in his approach; Jules Verne, who often referred to his works as “geographical novels,” often accompanied his prose with detailed maps of the settings.

One thing led to another and before long, the father-daughter duo decided to try and track down an original Jules Verne map, then another one. “We started buying to try and get a complete set of [maps by] Jules Verne, which it turns out is almost impossible, but we did it,” Crouch says proudly. “Then we bought another thing, another thing, and things like [maps from] Robinson Crusoe, Treasure Island, Gulliver’s Travels.”

As compelling as these maps of Lilliput or Skeleton Island may be, no one ever believed these places existed. Crouch finds the map of Poyais particularly intriguing because of how many people were utterly convinced in its veracity.

To understand why MacGregor would do such a thing in the first place it helps to know a little bit about his family history. His grandfather—also named Gregor MacGregor—lost everything in the South Sea Bubble of 1720, an economic crisis sometimes referred to as both the world’s first Ponzi scheme and financial crisis. “His grandfather was ashamed by being involved in this mess, and he never really recovered from it,” Crouch says.

Forced to make his own fortune, Gregor MacGregor set forth across the Atlantic Ocean with the British Army at just 16 years old. He wound up fighting as a mercenary for Simón Bolívar, the Venezuelan statesman who earned the nickname “El Libertador” for wresting several South American nations from Spanish control. After MacGregor left his wife and took up with Josefa Antonia Andrea Aristeguieta y Lovera, Bolívar’s famously beautiful cousin, he invaded Florida, which was Spanish territory at the time.

On June 29, 1817, MacGregor landed on Amelia Island with a few hundred armed men. Since there was virtually no one on the island to begin with, he easily seized power. “While he was in control of Amelia Island, instead of fortifying it and bringing in cannon, he invented a flag, stamps, [and] currency in an honor system,” Crouch says. “He was a little bit miffed when the Spanish came and kicked him off. He then went back to London, but inspired by his prototype with Amelia Island, he thought, ‘Well, maybe I could create a country.’”

Enter Poyais, the tropical paradise that never was. MacGregor claimed to have been made the “Cazique,” or leader of the country. He raved about the timber-rich forests, a local Indigenous population that for some reason loved British colonizers, and clean streams that glittered with real lumps of gold.

If that all sounds so absurd to be believed, his attention to detail may have kept him from being suspected. MacGregor did everything from designing fictional military uniforms to writing a guide book to the country under the pseudonym Thomas Strangeway. He even printed Poyais dollars—which prospective settlers could, of course, exchange for their British pounds.

“He was so convincing that 250 poor Scots went on board the ship, the Edinburgh Castle, armed with his guidebook to Poyais,” Crouch says. “They then spent two years dying in the jungle. Forty of them come back and stand for his defense to say, ‘No, we just got lost because obviously we didn’t find the land in the guidebook.”

Crouch suspects that MacGregor may have stolen the name for his fake nation from the The West Indian Atlas by Thomas Jeffreys. “By complete fluke, I had [a copy] kicking around when we got this map in,” he says. “It’s really rare.”

Luckily, that’s more or less his specialty. After decades of running Daniel Crouch Rare Books, he has access to a trove of antique atlases. “We open it up, and sure enough, on the map of Honduras, it names Poyais,” he says. “It’s not called Poyais in any of the other iterations, just on this one. It’s obviously a mistake, named after some people [the locals] called ‘Poyers.’”

When the British became increasingly suspicious, MacGregor took his tricks across the English Channel to Paris, where he raised nearly £300,000 from investors interested in Poyais. After wriggling out of a French court’s attempt to convict him of fraud in 1826, he took his act back to London. He ultimately retired to Caracas, where he died a wealthy man at age 58. It’s a tale almost too fantastical to be true—and, of course, it all started with a map.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook